“CEOs and business heads have a valued resource within the COO and business management community, which has proven essential.”

THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES

From ‘nice to have’ to ‘must have’ – the COO in ascendency

I first came across the role of ‘business manager’ when recruiting for Lehman Brothers in the late 1990s. At the time I was a partner in a new search business, Alexander Mann Global Markets, and up to this point in my career I had focused my efforts on middle-office and operations recruitment. I was approached by a client I had previously worked with when he held a managerial position within treasury. He had since been promoted into the front office into the role of EMEA chief administrative officer equities, and he now asked me to search for a VP business manager.

What struck me immediately was that this was unlike any other managed assignment, which were largely based on the directive of ‘find me three or four people doing this role elsewhere and I will hire one of them’. Here, however, the client’s opinion was that if this role did exist elsewhere in title, the person in the position would probably be undertaking very different tasks. I would, he directed me, need to find the person with an appropriate level of experience and particular competencies that could migrate into the role of the business manager. This wandering from the standard path was in itself a welcome break from the ‘square peg, square hole’ recruitment that had framed my daily activity since entering the world of banking recruitment in 1995, after serving as an infantry officer in the British Army.

The Lehman business management function proved to be a healthy artery of revenues and assignment opportunities up until its demise in 2008. However, it also put me on the path to further investigation and exploitation of this area of ‘business management’.

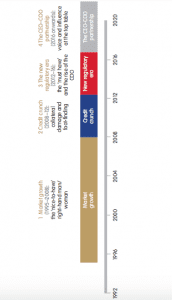

Within this 20-year period (1995–2016), I believe there have been four phases of development for the business manager, who carries various titles representing a role with common and core responsibilities: chief administration officer (CAO), chief operating officer (COO) and in some cases chief of staff (CoS). Worldwide, the banking industry has liberally distributed these titles, with many banks having tens, if not hundreds, of people holding them. More recently, however, some banks have scaled this back to help define the seniority of the COO, CAO or CoS, retaining the title for one person (or at most four, if regional COOs are appointed: Americas, EMEA and APAC). Barclays, JPMorgan and UBS have all renamed COOs except the global COO (within markets) as ‘business managers’. The four phases can be summarised as follows (see right):

Before the credit crunch, banking (specifically investment banking and the financial markets) experienced an unprecedented period of growth, although this later proved to be built on sand. During this period, few banks had an integrated or centralised COO function. CEOs and their business heads appointed a business manager to support them in the daily tasks of driving the business. Invariably this business manager reported to the business head directly, had no full or dotted reporting line elsewhere and was tasked, appraised and paid directly by the business. The role was generally unstructured and focused on facilitating and enabling growth, hiring the best people and directing capital investment into the support functions to ensure they could execute business support activities accordingly. The role looked externally, at new markets or new location opportunities, taking the vision of the business head and new products and realising this vision. Of course, not all business managers carried all these tasks; some were more focused on budgetary management, talent management or managing the relationships downstream into the infrastructure. However, even in these cases, business managers were generally regarded as ‘nice-to-have’ resource, whose immediate proximity to the business allowed them to catch the portfolio of work more readily. They were generally left to manage the relationships on behalf of the business with such functions as middle office, operations and technology.

All these were of course business critical, but in an era of extraordinarily high revenues, they were not of interest to the business and so were often dismissed as ‘back office’, creating a ‘them and us’ culture. This approach gave rise to a generation of bankers, traders and salespeople who paid little attention to the importance of support functions, who were disparaging about their role and unaware of its complexity and burgeoning cost. To be king or queen in banking (or even a member of the high court), there was only one path to follow – a career in revenue production. A career supporting revenue production would never lead to greatness, although remuneration was still high compared to people with comparable education and skills in other industries.

At a time of high demand and when banks had money, they were struggling to hire and retain good people. One result of this was that even staff in comparatively low-skilled roles within core operations were paid handsomely, whilst middle to senior managers often earned hundreds of thousands and operations’ heads into the millions, even though they generated no direct income for the bank. Not surprisingly, this uncontrolled wage escalation created a burden that has been carried forward to today. It is a resident item of consideration and focus for COOs and business managers, all grappling with falling revenues and fixed costs.

When the house of cards came down in 2008–09, it took the business-management function with it. In this period of bailouts, restructuring and downsizing, the business manager moved from being a ‘nice to have’ to a ‘not needed’, as banks looked for ways of reducing headcount and streamlining activities. As a search industry, we experienced a steady flow of previously well paid business managers now out of work. Growth and facilitating growth were no longer on the agenda, and as such, the COO, CAO and business manager were considered surplus to requirements.

For three or four years after this, the business management function was in the wilderness. Principal COO appointments remained in place, but the COOs and CAOs who had populated the broader business management function found themselves searching for a foothold to keep themselves in position or trying to find a role with a qualified mandate and purpose.

Some would argue against this suggestion, claiming that many COOs, CAOs and business managers remained in place, running the day-to-day activities of the bank, keeping the lights on and the wheels turning, even though they were struggling to hold an authoritative mandate while many business leaders fell around them. Even here, the COO remained largely invisible internally and externally amidst the turmoil.

It was only with the advent of new regulations, the by-product of the intense investigations and review into the banking sector post-2008, that the dormant roles of the business manager, COO and CAO emerged from their slumber. This was not marked by a quiet re-entry but rather a sudden step back into the spotlight. The COO’s part in this new chapter unfolded quickly, and a well defined mandate – a mandate of absolute necessity – was framed. In 2011–12, regulators issued a tsunami of new regulations, and the industry had to comply within specific time frames. Understandably, the regulators required this burden to be carried by the CEOs and the business heads, who needed to remain focused on revenue and wealth creation. What supporting role would help the CEO and the business meet these demands? The answer was simple – the COO, CAO or business manager. The business management function must be revived.

In this era, the COO partnered the CEO (and the business manager partnered the business head), executing the demands of the regulators. While the CEO and business heads retained accountability for all aspects of the business, the COO became responsible for ensuring it was being brought in line operationally. The CEO and business heads could thus continue to focus on delivering revenues in challenging markets, while their COOs focused their efforts on the control, conduct and governance agendas, to the extent that most banks subsequently appointed chief control officers (CCOs), reporting into the COO to bring a further focus on this business-critical area.

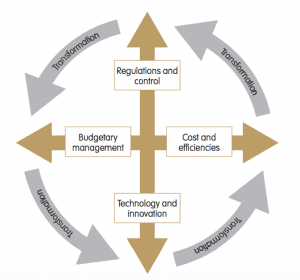

This hand-in-glove partnership brings together two people with very different skill-sets, but with a common aim. This is, in many ways, what makes the role of the COO and its relationship with the CEO or the business head and business manager unique to banking. The COO role is predicated on the need to meet these demands, and the skills to do so are framed by the book of work. It is very rare that COOs become a CEO, because they lack the prerequisite skills to perform this role, mostly associated with managing risk. At the same time, CEOs or business heads lack the skills and experiences to become an effective or accomplished COO, certainly in a stand-alone capacity. By 2016, the role of the COO was defined by four principal areas of work, all framed by transformation and executing change:

The challenge, of course, is allocation of resources and limited capital to deliver the change that will take the business forward, when presently the cost of meeting regulatory change, control and conduct consumes whatever capital remains. The skills required to be a successful COO are investigated later in this book, but it is important to mention the behavioural characteristics required to meet the demands of the role. Certainly these characteristics include an ability to thrive in a role embedded in ambiguity. It is equally important to have someone who is tenacious, yet possesses strong relationship management skills. This is not a job for someone who seeks an exclusive position in the spotlight, because the role will always be playing second fiddle to the CEO or business head. Much of what the COO does will not come to fruition for some time; indeed, the full implications of its value may not be realised until long after the individual has moved on from the role. There are few accolades for the COO, despite the weight of responsibility on their shoulders.

Four years into this regulatory transition, we see the first signs of a review of the COO role and the business management function. Additionally, the time, effort, resources and capital invested in building control teams (the first line of defence, 1LOD) would appear to be entering a period of interim maturity and consequent review, as banks look to adjust their models and seek more cost effective ways of refining and enhancing the control framework. The market-wide 1LOD design phase has led to such conclusions and has been accompanied by innovative technology development, offering new solutions and choice. It is an interesting period that the COO community is entering.

Alongside continuing to captain and lead the control and regulatory agenda, the COO’s role is now set on meeting new demands, driving innovation within the business and its infrastructure, or embracing technologies to retain and enhance competitive advantage externally. CEOs and business heads have a valued resource within the COO and business management community, which has proven essential. On one side, the recent ascendency of the COO has led to the role becoming more visible, responsible and influential. However, it is still not all-powerful. It has defined itself as a ‘must-have’ position but is still countered by the question ‘What must I have?’

Some look at this position as a staging post to future promotion to run a business or even to become the CEO, taking a step out of a revenue role to do so. Where businesses are aligning themselves front to back and bringing technology and operations back into the business, the COO role is defined more fully as a bank wide, front to back, fully responsible and accountable executive position. The COO sits on the executive board, but the role is unlikely to be a stepping stone to kingship.

It is in this period of further progression we find ourselves in 2016. Now is the time when the role of COO will develop, evolve and be further redefined. The new regulatory era bought the COO out of the shade and offered no place to hide, but conversely, as one of my clients stated, ‘It could equally be read that the regulatory era offers no place to hide for the CEO, more so as it is the CEO and not the COO who is accountable.’

Perhaps then the marriage of the CEO and the COO within banking is one that brings together opportunity and necessity, where neither party can hide. An effective partnership between these roles is therefore essential in realising their own success – and the success of the bank and the investors it serves.