Executive Summary

The CCO community meets each quarter at the CCO 1LOD Forum, run by Armstrong Wolfe, hosted on each occasion by a CCO and his/her bank. These forums are run in Toronto, New York, London, Singapore and Hong Kong and attended by 24 of the world’s leading investment banks from the U.S., Canada, Europe and Asia since 2014. These forums have been run since this date alongside and in hand with the evolutionary process that has led to almost all leading banks having a CCO or equivalent appointee by 2019.

The position of the CCO and the roles embedded in the office of the CCO are now well established. Most leading banks have this executive role embedded in the business, all be it in name it may vary (Global Head of Business Controls and Conduct for example), reporting into the Markets’ COO. Apart from one where the CCO reports directly to the Global Markets CEO, arguably a statement of the importance and independence of the control and conduct function.

With the genesis of the CCO role being in Markets, it is not surprising this concept has consequently fed into aligned areas of Financial Services, with Banking and Asset Management embracing this mandate, now seeing it as an evolving and key role within the front office’s business management leadership team. This is an important factor, as this is creating additional career opportunities for Markets’ staff, as Bankers and Asset Managers access the Markets’ 1LOD talent pool to hire staff to help lead the development of their own 1LOD functions. This demand for experienced control, conduct and regulatory staff is also aligned to the demand within Markets, as many of the smaller banking franchises are investing in establishing their own 1LOD functions, following a well-trodden path by the industry’s leaders.

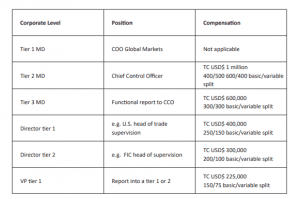

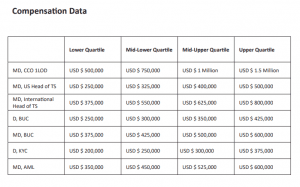

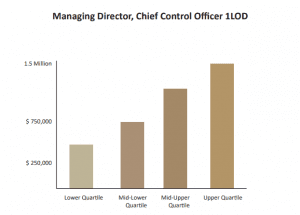

Importantly no one bank aligns or staffs its 1LOD function in the same way and to this end direct comparisons from one bank to another in role and mandate and in consequent compensation is challenging. Any data provided is therefore at best highly representative, but never wholly accurate.

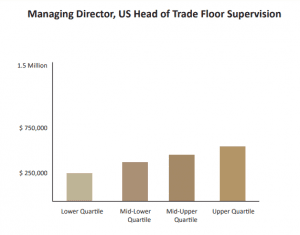

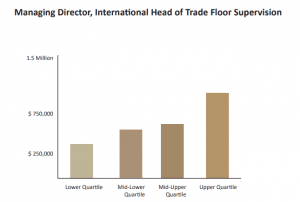

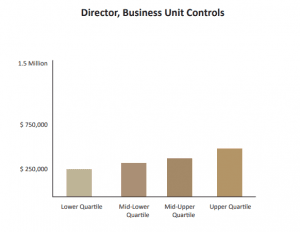

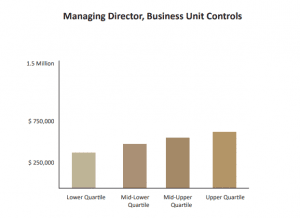

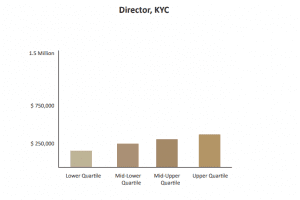

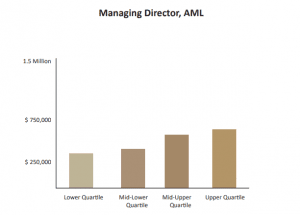

To this end the most reliable data (as a reference point where any bank is seeking to be competitive when hiring staff and/or in paying and therefore retaining its staff) would be to look at mid-upper quartile within front office business management, and roles defined as being within the office of the CCO.

Executive Summary

The following table is therefore useful as a clear indicator of compensation (basic and variable) within the Markets’ sector (with detailed analysis found in later in this report):

(note: this report will be distributed to the attending banks of the CCO 1LOD global community)

“The job of the CCO is to know which controls work and which don’t.”

THE CHIEF CONTROL OFFICER: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

Executive Summary

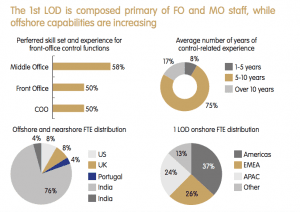

As global leaders in executive search for banking and markets business management, Armstrong Wolfe has a unique insight into the profiles of its leadership. The following is a summary of the skills and experience of this leadership group, as well as the evolution of the function itself. We concentrate on the global leaders of the front office control function for markets within twenty top tier global banks.

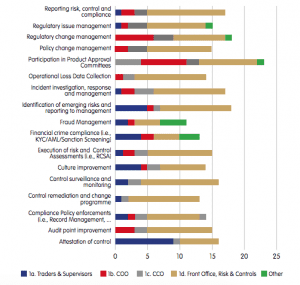

Within this group, there is a variety of job titles, including Chief Control Officer, Head of Markets Risk and Control, Head of Business Control, Head of Supervision, Operational Risk, Financial Crime, Conduct and Control, or a combination of these.

The skill sets are varied, with a few accountants and one lawyer, but a front office business management background was predominant. This is unsurprising as the role has recently been separated out from the COO role. The average length of tenure was around two and a half years and there was limited experience of working abroad. About a quarter are women. Only one had a trading background whilst most are graduates, but the lack of a degree is no barrier to rising to these positions. Overall it is clear that an integrated and varied background around the skill set seems best suited for these roles and typically persists. That ambiguity is reflected in that a majority of people have risen through the front office operational, non-revenue generating ranks themselves.

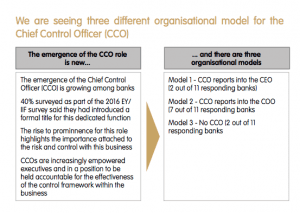

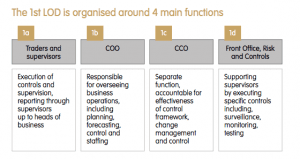

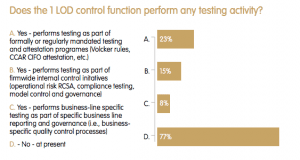

Next, we consider the evolution of the role itself and possible future scenarios. We draw on the EY First Line of Defense benchmark survey of seventeen major banks. This was presented at the Armstrong Wolfe Autumn 2016 Business Risk and Control Forum, and we enclose insets from that survey. It was published as ‘Front office control functions, what’s next for capital markets banks?’ in February 2017.

The Role

The front office COO role evolved after the regulatory response to the financial crisis of 2008. The sheer quantity of administration involved meant that the CEOs of markets businesses leant ever more heavily on this function. It included responsibility for strategy, business development, finance, administration, resilience, and front office risk and control. However, in time, especially with the appointment of Chief Risk Officers, these functions began to fragment. Administration began to be taken over by a CAO, finance sat with a CFO, and the business control function itself began to be taken up by people with a title such as Chief Control Officer. This had always been a significant part of the role, but became even bigger, dealing with the major regulatory issues of each country, region or globally from an operational and conduct risk perspective.

The sheer volume of controls, and the development from manual to technologically based systems, required someone to act as a conduit and take a more strategic approach. The focus became one of risk and control, rather than expansion into new markets or driving efficiencies. This involved major programmes of change and transformation, including the development and upgrading of surveillance and supervisory systems. Both regulation and ongoing market events drove the need for investment into control measures within the business. This has attracted people with a variety of backgrounds, including legal, finance, audit, risk and change, as well as core front office operational and business management backgrounds, and more recently, traders themselves.

The First Line of Defence

There was a common point of change after the LIBOR and then the FX fix scandals. The question was asked of markets leaders, are you in control of your business, and if so, who specifically is it who owns and leads this business critical effort?

In addition to what was being booked and how, a framework around behaviour, conduct and activity became an essential part of management. There was the development of communications surveillance and activity monitoring, such as simple, but potentially important alerts that noticed when people were working late. A rule book was developed to cover all the stages of sales and trading activity. The support functions of compliance and audit were not targeted to examine these activities, and so it became the responsibility of the front line.

In addition, effective supervision required someone who really understood the communication and behavioural signs to monitor. A desk supervisor was the most effective person to do this, especially in terms of pastoral care and mentoring, which the support functions were not really positioned to do, but a framework was required in which to do it. Thus, the first line of defence was established, with control officers setting and managing the implementation of that framework. By 2018, different institutions were at different stages of the establishment of this framework, and had adopted different models of implementation.

Current Status: 2018

These themes are relatively consistent, although a few organisations have maintained the control function within the COO role or even at one leading bank, under the CFO in the front office, with a very strong second line. However, organisations differ by whether the CCO concentrates on the more strategic elements, with a major change agenda, or maintain a focus on pure supervision and governance. Some organisations have the control officers embedded within the individual businesses, reporting directly to the head of desk, with a dotted line to the Chief Control Officer or equivalent. Others have the individual control officers directly reporting to the Chief Control Officer. What is essential is that they must be good at dealing with people, influencing them to adopt the control agenda, and persuading them that it is in the interests of their business.

There is a major job of translation and ambassadorship to be done in applying the demands of the regulator and corporate leadership to the individual desk. The ability to be both a change agent and apply a control mindset requires substantial personal qualities. It can take around five years fully to respond to new regulation, and there will be strong views on how things are done within each jurisdiction. The difference between the US rule-based approach and the UK principle-based approach, for example, presents a challenge to ensure that controls are enforced consistently.

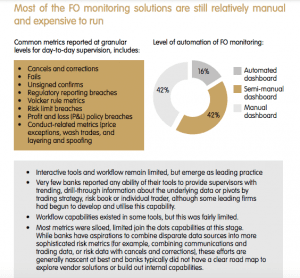

A good control model is one that implements a process of inquiry, testing and review. This may be regarding financial crime or client onboarding, for example, and so may bring in people with a compliance background, and involve a migration from the second to the first line of defence. This also involves significant technological input, providing big data solutions, for example, in first-line surveillance. This, however, requires an experienced eye to distinguish between a whole series of false positive results and a genuine concern. In general, the front-line control function has to take a more integrated approach to overcome duplication, gaps and fragmented solutions.

The first line ultimately owns the risk and requires a practical solution to its day-to-day management and governance, especially with the implementation of the senior manager regime. Ultimately, there is a need to demonstrate to the regulator that the business has understood its internal risks, and that they have put in place an appropriate control framework. Working across many global locations and jurisdictions obviously poses a challenge in establishing a consistent approach, but this is one the CCO must face.

Whilst there is a formal annual assessment of risk and controls, in practice this is done on a monthly, or more frequent basis. The job of the CCO is to know which controls work and which don’t, and to turn an overarching framework into a practical risk assessment and controls framework. This is the work of translation and integration that needs to be done. The practical basis is the one in which the control function helps the business, for example suggesting that five books may be run rather than 95, or that daily closing routines are followed on time. Procedures must be simple, orderly, effective, commercial and compliant, and the ones that don’t work must be eliminated. The CCO must be able to understand the different audiences and how they think, working with the other corporate functions front to back, though front office, operational risk and compliance. The front line owns the risk and so must lead this process.

Regarding background, front office experience tends to provide the ability to sell what they are implementing to internal clients and into the business. It is important, however, that this does not just involve taking people who are underperforming, and that this group is constantly refreshed with people who know the current state of the markets and have up to date contacts. Auditors tend to be used to asking difficult questions and dealing with the response, and lawyers have a strong intellectual contribution to make. Ultimately, someone who is comfortable with change is essential.

Future Development

There is some debate as to whether the function will remain separated from the day-to-day role of the COO, or whether it will be reintegrated once the current phase of remediation has been implemented. If the testing is not core to the business then it could revert to compliance, or in part into an operational risk function with an enlarged remit. The alternative is to upgrade the assurance team with a fully fledged audit, to a Federal Reserve standard. This may involve hiring auditors or people with a finance or legal background, while surveillance may be staffed by security service type people, technology gurus or ex-traders themselves.

In all cases the industry’s capability to manage and use data effectively will define the ultimate solution and the timing of its development and implementation. Whilst technology will deliver this shift, however, it is equally important never to forget the unique and ever changing component in this equation, the human point of contact.

There has been so much regulatory change, there will be more in the future and the demands are so great, that it is not easy to see when (if ever) these control functions and their processes and policies may revert to its pre-existing location, under the direction and ownership of the business COO.

Typically, the front-line function reports through the COO’s office into the Head of Markets, Banking or other, who is collectively responsible for all activities within his or her business and will be kept fully up to date with each investigation, and will feel this responsibility more so under the senior manager regime. The second line is viewed in an advisory capacity, one of policing, but while the approaches are very different, the objectives are the same. This fact is very important, as all functions ultimately have the same mission, to ensure the business is protected from poor practice or malice.

Front-line testing and assurance needs to be light touch to avoid unnecessary repetition and bureaucracy, the second and third line tasked to be constructively intrusive. However, as fines increase, problems still need to be solved urgently. Surveillance and engendering a culture of whistleblowing are essential in this regard. The relationship with the regulator is key to the front office perspective. They need to see friendly faces and have open discussions, but changing the culture remains the long-term objective, to put each bank and the industry on a firmer footing.

The technological requirements of modern market activity are shaping a need to move towards real-time trade surveillance, especially in conjunction with the implementation of MIFID II in 2018. This depends on the development of external systems and innovation, such as Forcepoint and Nasdaq SMARTS, but also on the development of internal platforms and capabilities. In this context, facing a common non-proprietary challenge, within a cost containment environment, cooperation and collaboration is a viable and valuable route to explore and exploit, enabling the banks to more effectively access and embrace the possibilities being presented by the growing FinTech sector.

Also relevant is the monitoring of chosen trading locations, as well as client suitability. This is further changing the relationship between the first and second line, as is the impact of changes affecting cross-border flows, such as Brexit. This contributes to the need to develop a legal entity level framework as well as a booking level perspective.

Conclusion

The role of the front office CCO is to fulfil the day-to-day execution of the supervision and governance framework, establishing consistency and evidencing for the internal and external requirements of the regulator, compliance and audit. Establishing this on a sustainable basis is crucial, while they must keep a focus on technological innovation and solutions. The activities of this function will continue, but when and if it is reintegrated into the COO role is a moot point, as is the future state of the 3LOD concept itself.

There is some advantage to having someone with a C-Level position who is thus able to carry the authority to implement the front to back change required and to manage the associated investment. Such senior cross-functional executives should be able to secure, even command buy-in, at the highest levels of the organisation, as well as shape that agenda for the future, as human innovation and abilities will continue to test and navigate the controls implemented and poor practices and events will unfold, emerging risks and vulnerabilities now being the primary item on the CCOs’ agenda.

‘It is time we look forward, get on the front foot, as we have all spent and will continue to spend time and money on mitigating the failures of the past. We must prepare to meet the demands of the future, where many emerging risks are almost certainly things we as an industry have already done.’ (Global Business Controls Officer).

In this context, the role of the CCO and ownership of the control and conduct agenda has years of work ahead. Poor conduct in banking is not a new phenomenon; there is evidence of it throughout the history of the banking industry. Importantly, however, in an era when social media and technology drive communications and perceptions, the CCO’s role in maintaining and building a robust control framework and in rebuilding confidence in a beleaguered sector remains central. In part, you could argue, re-establishing the reputation of the industry is reliant on the success of the CCO community.