“The key to unlocking the door to a successful inter-bank collaborative application is understanding the business motive behind it. Cost saving is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Successful collaborative ventures to date have typically been regulatory driven, such as CLS. A successful business-driven motive would include either some revenue upside for the participants or something that could only be achieved with more than one participant. CGI believes that there are a number of applications in the latter category that could be considered, such as netting of the payments leg of nonFX trades. As a next step, the industry should establish a set of open forums where such initiatives could be tabled.”

JERRY NORTON, HEAD OF STRATEGY, FINANCIAL SERVICES, CGI

RESHAPING THE CONVERSATION WITHIN OPERATIONS AND TECHNOLOGY – THE TIME IS NOW

The Q2 2016 Armstrong Wolfe COO forum was attended by over 50 COOs within markets and regional bank wide COOs in London and New York. Participants discussed how the COO community should seek to reshape the conversation with operations and technology.

The debate took place at a time when many banks were realigning their business support functions and, in some cases, taking back direct management of these areas. The discussions were also held in the ever-present shadow of cost and efficiencies, especially in the case of struggling investment banks, where revenues and profits were in sharp decline with no sign of better times to come.

For many years, banks actively invested in low-cost centres and, to a lesser extent, outsourcing, to bring down the capital provision for their infrastructures. Traditionally focused on core operations and technology, this staffing strategy has now extended into risk management and parts of the front office. This was (and is) an understandable strategy, although wage and real estate escalation gathers pace quickly as each location reaches a critical mass of companies. This led many banks to source new locations and territories in the hope of winning a first-entry advantage. Examples of such locations include Poland and other eastern European countries, which offer a mobile, well-educated talent pool within the European Union, as well as being comparatively near Europe’s principal financial centres of Europe and London and in a good time zone to bridge the Americas and Asia. In addition, they retain comparatively low compensation and property costs. Centres such as Singapore and Ireland may have been groundbreaking for this headcount migration, but they are no longer viewed as low cost; India remains the leading light on the low-cost spectrum, but is now facing increasing competition from other countries:

“Outsourcing has generally been done to save money, not to be more effective or efficient. This has resulted in large distributed teams operating in a waterfall development environment on large code-based applications. Cheap is good, but sometimes it just doesn’t work. In my opinion, outsourcing should exist with the more agile onshore smaller development teams. The solution is to take pieces of both, in a balanced portfolio.”

While the effort to outsource to such locations continues, there is a growing opinion that this course of action is not the solution to all cost and efficiency issues. What alternative is there? The answer lies within technology innovation and the point in its own evolution when full automation of any operational process can be achieved. If this innovation is combined with cross-bank collaboration and/ or investment in technology and shared utilities of non-proprietary processes, it is possible to move towards the endgame of cost and efficiency. Low-cost centres are used to drive down costs, with the labour and real estate arbitrage, but banks have not realised efficiency gains because antiquated and cumbersome technologies remain in place:

“The larger-scale innovation opportunities (particularly around the creation utilities) are found in the areas that banks have already outsourced. This creates difficulties as there are now lots of parties involved and the model looks to erode the rationale for many of the outsourced providers. A turkey rarely votes for Christmas.”

Low-cost centres have delivered good results in the short term, but the technology now exists to deliver advanced processing systems, so banks now need to invest in this to improve efficiency as well as cost. In an environment where capital for such investment is scarce, sharing the cost would appear to be a logical option – and this leads to a creeping sense that we are at a turning point in the evolution of low-cost centre investment and management. Cost demands are pushing us towards cross-bank cooperation – a step that would mark a dramatic shift in the operating model of the industry. As one COO put it:

“Technology is the parasite eating the host, where the required medicine is available to cure and rid the body of it, but it is either too costly to access, or once the pill (the solution) is in hand, the host is too fearful to take it.”

This forward-thinking sentiment came up during the debate and had strong supporters. However, there was a pessimistic echo, as some participants were not confident that this collaborative leap could be made. The dissenting voices were not being negative for the sake of it. These COOs were either working or had worked at banks that held to the belief that there is a competitive advantage to retaining self-built, proprietary technologies. There remains an inherent mistrust between the major players when it comes to the idea of working together on key initiatives, especially those that might deliver an advantage to small or medium-sized institutions (which could see themselves coming together more readily to realise a common goal):

“I think organisations are struggling with control and what gets delivered through an innovative construct. Typically, third parties bring capital, concepts and some raw resources, but they generally lack the subject-matter knowledge. Getting this balance right is key.”

The discussion hung on this point for some time. While central to the debate, the issue appears to be not just the use of low cost centres as part of the staffing, efficiency and cost strategy and what the solution could be. There are also questions about functionalisation (across the bank’s various divisions) and the governance and direct ownership of this investment, operational headcount, and ability to mobilise and direct the resource. This would leave many businesses feeling disconnected, with no line of sight into their support functions and no influence over the spend of their investment.

The COO group agreed that it was less a question of cost than one of productivity, the return on investment and the ability to directly influence this significant outlay. “There is a Chinese wall built around the operations and technology empire”, one COO explained, “which prevents us from directing its energies to address our business needs effectively.” Another COO added: “The invoice for its [operations and technology] services is presented as if a fait accompli, where we are assured we are getting the best possible return on our investment and there exists no viable alternative.” This statement had some substance, as this COO had been schooled in operations before moving into the business some 20 years into his banking career. He went on to explain: “This rite of passage seems predicated on the assumption that the only solution is self build, internal development and in-house operational support, which simply doesn’t ring true in today’s technologically advanced economic community.”

A COO moving from the front office into a lead role in operations contributed to the dialogue: “What makes it more complicated is not the allocation of costs within markets, which are comparatively straightforward, but the allocated costs from elsewhere in group. You intuitively feel these costs, if investigated, would find favour to group and not us, as the end user of their services, which we have little or no influence to change.”

Two key questions had taken shape within the debate at this point:

1. Would the interests of the business be better served if it ‘owned’ and directed operations and technology?

2. Are there better technologies and/or solutions that could offer a different resolution to the traditional in-house, catch-all proposition?

In line with these two themes, there appeared a view that the industry needed to do something to break the status quo, to look beyond the solutions to date and recognise that cross-bank cooperation and collaboration in non-proprietary areas of the infrastructure were no longer theoretical concepts for discussion, but truths that should be exploited.

Where has this idea of finding a mutually beneficial solution come from? Where is there evidence that this breaking of the mould could work? SWIFT and CLS were offered as examples, showing that a spirit of cooperation could be found in previous ventures (although this was more about necessity than a desire for cross bank innovation and collaboration). This success is not unique within banking, but is sadly one of a small handful of examples banks coming together for the common good. The benefactors of these limited initiatives are clients, investors, the banks themselves and the industry as a whole:

“We should be looking to change the processes so that some of the things we are currently doing become obsolete. By going through the automate phase, you can damage the value proposition, as the ultimate saving post-automation isn’t large enough to fund unwinding all the automation.”

So why is this the case, when the benefits are understood and widely acknowledged? “The problem is us”, explained a global COO Markets of one European bank. “No one else, not the challenge in itself, but us.” Another COO added:

“The challenge we have, as COOs, is that we don’t own operations and technology, but we wear the problem. There invariably exists a healthy tension between direct and indirect ownership, although there does exist an overarching focus on cost, efficiencies and discipline. Within the business we have a stated corporate policy that we are committed to adding value to shareholder after allocated costs, which has engendered a greater appreciation of the front-to-back responsibility, although we know still the trader, the heads of desk still hold to a narrow view of what is important, being the customer, price of the trade and its risk profile. The question here is whether we could work with our competitors on areas of potential benefit and whether we need a gun to be held to our head of a regulatory demand or as we find ourselves today, cost, to make it happen. I think we probably do.”

Further discussion offered a little more colour to this statement. He went on to explain that banks, certainly the leading institutions, clung to an ill-informed and incorrect assumption that retaining singular control over core operational processes and associated technologies created some form of competitive advantage:

“This misunderstanding was perhaps understandable in days gone by, when cash was plentiful and the direction of travel of the products was increasingly complex and the technologies were simply not in existence to offer a cross-bank or industry solution. Today however, these technologies do exist, and so does, arguably, the necessity to act.”

This is not necessity by law or regulation, but necessity by cost, control and regulation, as well as an increasingly competitive landscape, with ‘challenger banks’ and the dawn of the Fintech era. It was this statement at the start of the debate that helped frame it perfectly, capturing as it did the spirit of the subject and directing us towards an investigative dialogue. How indeed can the COO community reshape the conversation with operations and technology to deliver a change in direction, if necessity now demands this change? Equally, if this change is needed and was to happen, why does responsibility for driving it lie with the COO community? And do COOs have the power and influence to do so?

The fact is that most COOs are not empowered to initiate such a change, and neither do most directly own the infrastructure. They do, however, carry an influence that flows both up- and downstream. This pivotal position, sitting astride and between the business and its infrastructure, affords the COO community the opportunity to speak for the business at the same time as managing its expectations on success. As a collective … as a community … this voice becomes louder and carries greater influence and authority. If COOs can combine this with objectivity and a desire to do best for the industry, then success could be realised:

“Many organisations have structures whereby a support function’s IT costs are allocated to the support function, which in turn then totals its costs and allocates to businesses and regions.”

The group moved towards this position and largely accepted that while this may not happen during the group’s tenure, it remained an opportunity – an obligation, even – to try and make happen. “In this case”, I asked, “in what areas or common ground, common purpose, non-proprietary, could you sow the seeds for cross-bank, industry-wide collaboration?” Data warehousing and supervision headed the list of such opportunities, with supervision taking top spot, as it was an immediate need. The necessity had been agreed. It was now left to see if this group of executive influencers could find sufficient common purpose to take the first step and perhaps, by drawing this line in the sand, take the industry in a new direction – one that may contribute to its long-term security.

Before finalising this article, I presented it to one of my principal contacts, who added further to the debate:

“Outsourcing was generally done to save money, not to be more efficient or effective. However, while cheap is good, sometimes it just doesn’t work. Outsourcing should coexist with the smaller, more agile onshore development teams. The solution is better with pieces of both in a balanced portfolio. Innovation is harder to nurture in a large outsourced waterfall team than it is in a small agile onshore team. I don’t really see an issue of self-build and proprietary value being friction points. There is a general feeling that automating these processes is the best solution. However, my view is that we should change the processes so some of the things we are currently doing are obsolete – remove, not automate. Personally, I would mandate that a cost could only ever be allocated once. Many organisations have structures where support functions IT costs are allocated to the support function which totals its costs and allocates it to businesses and regions. This makes it almost impossible to track which resources are working on what within that function. As support functions are becoming more directly aligned to business units, this should help. One final point on the new aligned model. I think in many cases now, COOs do own operations – they just haven’t realised it yet, and they lack the time and expertise to invest in these groups to help resolve their problems. The COOs are also struggling in some cases as the model shift towards decentralised structure is eroding some of the synergies that had been put in place by the previous global support functions. These are not deal-breakers, but they do need to be acknowledged and resolved.”

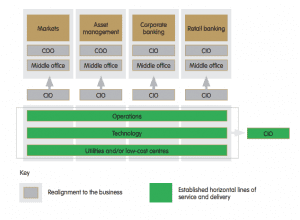

The realignment of operations and technology

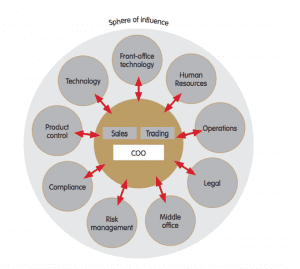

The sphere of influence of the COO