AN INTERVIEW WITH JOE NOREÑA ARMSTRONG WOLFE ADVISOR WCOOC AMBASSADOR

HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL (HBS) CRISIS MANAGEMENT FOR LEADERS

Joe Noreña, Armstrong Wolfe’s Business Advisor and WCOOC Ambassador joined the Harvard Business School (HBS) Faculty and other alumni in a 5 part program on Crisis Management for Leaders through the COVID-19 event. The programs were:

Program1: COVID-19 as a Novel Event and Risk Management Framework

Program 2: Coping with Sudden Changs in Cash and Availability

Program 3: Structuring the Organizational Response

Program 4: Recognizing and Managing Novel Risk in your Supply Chain

Program 5: HBS Case Study: Chilean Mining Rescue and Summary

For each program, Joe captures a summary of the dialogue in order to share with the Armstrong Wolfe COO / CCO community In ’Structuring the Organizational Response’, Joe summarizes what was learned regarding a team’s performance during a crisis, how to manage this situation and why a crisis situation may be a time to innovate.

Structuring the Organizational Response

Faculty: Professors Amy Edmondson and Dutch Leonard

1. Introduction

Over the course of three weeks (March 20-April 10), Harvard Business School (HBS) faculty ran a five-webinar series on crisis management through the COVID-19 event. The coronavirus outbreak has disrupted every organization and each of our lives in unexpected ways. For business leaders, managing this specific event risk and confronting the associated uncertainty and change has been complex and all-encompassing.

This paper captures my summary of the third webinar for the Armstrong Wolfe COO/CCO community. I hope to give you, as leaders, a time to stop, take a breath, and reflect on the powerful guiding principles shared by HBS faculty members and alumni business leaders to help you manage and lead during these uncertain times.

Returning to the risk management framework introduced in Session 1 (see my summary for more information), HBS faculty delved into issues of process and workflow management for teams during crisis situations. Through consideration of the Columbia Shuttle case study, we discussed the question of how to lead productive, problem-solving team discussions in crisis situations and the importance of emphasizing inquiry during important team deliberations.

Professor Amy Edmondson, who studies teaming, psychological safety, and organizational learning, led the session by focusing on how to help teams think about crisis management as a time for innovation. Organizations need to create the conditions for successful agile problem solving — before, in preparation, and during a crisis. Webinar participants spoke on how people were feeling during this crisis and the issues arising regarding teamwork. For a deeper dive, see the webinar recording link at the end.

2. What Issues Are Arising With Your Team?

Participants shared that their teams were getting tired but remaining positive. However, cracks are beginning to form because of the stress, high pressure, and uncertainty. As the work day progresses to some form of normalcy for people, questions are emerging, such as, “How do we deal with the ‘medium-term limbo’ as daily updates become somewhat stale?” and, “Do we keep to the same daily structure?”

Leaders are being challenged with keeping everyone informed while avoiding too many people participating in certain meetings, making it hard to make decisions. However, they’re focusing on their people during these times by creating forums to hear all issues and by providing a healthy physical and mental environment.

In some cases, organizations are creating new smaller groups to start thinking and planning for the longer term and the restart. This is moving them from purely firefighting to thinking about what positive steps can be taken once they get through this. This has been helping with the mental challenges being faced by all.

3. Understanding the Organization During a Crisis

Teams do not always achieve their potential during such times. What is it that keeps one’s core team from performing at its best during a crisis? We can attribute much of the challenge to the reality of ‘process loss’. In the social psychology of groups, this refers to any action, operation, or dynamic that prevents the group from reaching its full potential, such as reduced effort (social loafing), inadequate coordination of effort (coordination loss), poor communication, or ineffective leadership.

Some examples of process losses provided by webinar participants included:

• People struggling with, “What’s in it for me?” versus “What’s in it for us?” Leaders who keep people focused on the ‘us’ will help in managing people’s anxieties.

• Exhaustion stemming from lack of clarity and certainty.

• In some cases, people are not even part of any team, as they had been working alone previously and are now working alone from home.

Minimizing Process Loss Stemming from her study of team decision making in fast-moving environments, Professor Edmondson shared a framework to minimize process loss through Leadership, Being Directive, and Psychological safety.

Leadership

In a crisis scenario, leadership needs to be distributed across the organization; it cannot sit only with the CEO. There needs to be leadership everywhere, and it needs to be agile leadership. In times like this, one needs to enact in a network of agile teams, which in some cases is unnatural for an organization. A leader also needs to extract the wisdom of the team(s) by ensuring it is diverse as opposed to homogeneous.

Being Directive

Be clear about content and how the team should work. For example, create clarity about who is working on what, and who needs to be in the office instead of working from home (and why). As usual in dealing with the crisis, keep your decisions and communication aligned with your company’s values and goals.

With certain unknown scenarios, communicate that you are shifting to an exploratory/experimental mode. On certain actions, lead your discussion toward discovery, designing a test, and then pivoting or persevering accordingly.

Psychological Safety

Be aware that, at times like this, interpersonal risks are at their highest. Interpersonal risk refers to concern that others may not think well of oneself and associated rejection or humiliation. In a tribal setting, rejection means one will starve and die.

An interpersonal risk mindset will shift one from ‘performing to win’ to ‘performing not to lose’, which hurts innovation.

Some examples are:

• The feeling of being seen as ignorant: “I am not going to ask a question.”

• The feeling of incompetency: “I do not want to admit my weakness.”

• The concern of being intrusive: “I will not offer ideas.”

• Worries about sounding negative: “I do not want to critique the status quo.”

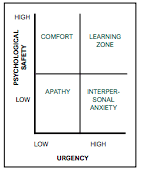

The diagram below depicts an organization’s behavior during high and low points of psychological safety and urgency. As the diagram shows, during a time of crisis, the biggest risk occurs when the organization is performing with Interpersonal Anxiety, a place of very low psychological safety but high urgency. The ideal place for an organization to operate from is the Learning Zone, where everyone feels psychologically safe to act fast with uncertainty.

The Columbia Shuttle study showed the risk of NASA not having this psychological safety, limiting the ability for people to speak up during a missioncritical meeting.

Factors discovered in this case study included:

• the hierarchy getting in the way

• a history of successful execution

• failure to meet goals being seen as a weakness, and

• having a culture of intense pressure to produce.

These were some of the issues that prevented the organization from operating in the Learning Zone, ultimately leading to disaster.

4. How Do You Minimize Process Losses?

Ideally, the foundations listed above should be built before a crisis, in order to avoid ambiguity on these topics. When things go wrong, it is natural to blame. With proper preparation, teams can perform in a joint problem-solving orientation, learning and creating knowledge together for the organization. In a crisis, this can be challenging for organizations unaccustomed to this mode of operation.

Working in the Learning Zone means equating execution with learning.

It includes:

• acknowledging that there are many unknowns

• bringing in subject matter experts

• lacking a fixed set of metrics

• doing things that have not been done before

In times of crisis, leaders need to be thinking of motivators to help people resist interpersonal risk. Lead with the mindset that we are all dealing with something larger than ourselves. There is a need to model humility and fallibility to demonstrate the behavior that is acceptable during these times. Showing that you’ve made mistakes before will convey that you are human and relatable. Asking genuine questions will make the team feel that you are curious about their thoughts and that those thoughts are valued. Seek to understand who in the organization may feel inhibited from speaking up with concerns, questions, ideas, bad news, and errors … and ensure their voice is heard.

Another helpful approach is to assign a devil’s advocate. Several studies have shown that having a person or group playing the role of devil’s advocate, will gives them the freedom to think and be the voice that will be ‘free’ to challenge in certain environments, committees, or hierarchies

5. How Do You Build Psychological Safety?

Set the Stage

Set the stage by providing transparency about what we are up against. Move from blueprint to brainstorm, going from the routine and well understood situation, to a customized/complex situation, and finally to a place of novelty and unknown where the team is innovating. Uncertainty goes up, so failure and learnings will also increase.

Invite Engagement

Ask the right questions rather than trying to have all the right answers. Good questions help people focus on the issue, invite the best thinking, and provide space to challenge it. Do not ask Business-As-Usual questions. Some examples of good questions are:

• What are we missing?

• Who has concerns, and what are they?

• What are you thinking?

• Who has a different view?

Deepen the discussion with questions like:

• What might happen if…?

• What leads you to think that way?

• Can you explain further?

Responding Productively

Make your response appreciative and forward looking to keep the momentum going. Alan Roger Mulally is the former president and Chief Executive Officer of the Ford Motor Company. He led the organization during the late-2000’s recession and returned it to profitability, making Ford the only major American car manufacturer to avoid a bailout fund provided by the government. During the dark times, Alan made it clear to everyone that he wanted honesty, no matter how bad the news was. In one example, when he was shown a chart that was heading in the wrong direction, his productive response to the presenter was simply, “Mark, thanks for that clarity on the issue. How can we help?” At the next update, the charts looked like a rainbow.

6. Closing Comments

The organizations that tend to succeed in this type of environment display leadership that:

• focuses on core values

• recognizes we are in a novel circumstance that requires experimentation with certain decisions

• sets up the right structure and cultural environment, and

• manages the workload.

They set the stage for being honest when they don’t know the answer in the moment. They invite engagement and foster productivity by showing empathy. As the extent of the COVID-19 impact becomes more real for people, the closing comments by the faculty to their former students become more touching:

• Stay safe

• Pace yourself

• This must be done. You can do it. Only you can do it.

Harvard Professors

Amy C. Edmondson is the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at the Harvard Business School, a chair established to support the study of human interactions that lead to the creation of successful enterprises that contribute to the betterment of society. Edmondson has been recognized by the biannual Thinkers50 global ranking of management thinkers since 2011, and most recently was ranked #3 in 2019. She also received that organization’s Breakthrough Idea Award in 2019 and Talent Award in 2017. Her most recent book, The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation and Growth (Wiley, 2019), offers a practical guide for organizations serious about success in the modern economy and has been translated into 11 languages. Herman B. “Dutch” Leonard is George F. Baker Jr. Professor of Public Management at the Kennedy School, as well as Eliot I. Snider and Family Professor of Business Administration and cochair of the Social Enterprise Initiative at Harvard Business School. He teaches leadership, organizational strategy, crisis management, and financial management. His current research concentrates on crisis management, corporate social responsibility, and performance management.

Webinar link

https://www.alumni.hbs.edu/events/ Pages/crisis-management.aspx#popup