As we move through 2018, now is the time for the COO community to seize the opportunity to shape the banking industry of tomorrow and address the imbalance created by the pursuit of profit over purpose in previous years.

How this can be done, and where the future of banking rests, are key questions to be answered.

The challenge for the banking industry today is for a new phase of optimism to be discovered, allowing for a liberated pursuit of profitability and the benefit for all.

The industry needs this change as does the worldwide economy. This phase must be led by innovative, intellectual and inspirational leaders who are bound by ethical behaviour and principles. Just as the Captain of a ship leads the vessel, it is the helmsman that steers it; as the pilot flies the plane, the navigator directs it; then it is the CEO who sets the vision and drives the business, but the COO ensures it sails to calm water in good order.

Since the Credit Crunch, most acknowledge that the role of the COO has morphed into being a CAO throughout the interim new regulatory era. The office of the COO has been tasked to meet and deliver upon the seemingly unlimited book of regulation imposed upon the banking industry by ever-vigilant and empowered regulatory bodies.

As we run into mid-year, COO attentions are turning enthusiastically to assess how they can support revenue creation, but whilst this is a desired change of direction, the challenge of delivering lasting cultural change is still to be realised.

In both cases, but specifically in relation to the culture and the conduct agenda, it is contended by some enlightened and optimistic COOs that there exists an opportunity for the COO position to become more empowered to directly support the CEO, and to be given the explicit mandate to own the execution of the CEO’s stated purpose and the consequent cultural change programme.

In doing so, the COO becomes the ambassador for conduct, behaviour and ethics and, as such, will be charged with delivering cultural change (on behalf of and in partnership with the CEO and the business, not as a servant to it).

If this mandate is held by all COOs, and if the CEOs collectively see the untapped potential of the COO function, then an industry-wide and consistent approach could be achieved, with all COOs adhering to the common goal of raising standards and cementing cultural change.

It would not be the total solution and it is not the silver bullet, but it would help in no small part.

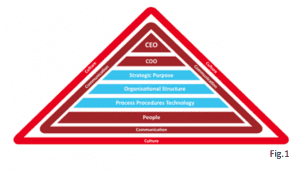

Note: The CEO needs to be a ‘people person’, not an extrovert. They should be someone with empathy and a connection enshrined in their leadership style. The CEO must additionally partner the COO in the definition, communication and pursuit of purpose, which through effective messaging, helps to define and carry an organisation’s culture. (See fig.1)

Is this too big a mandate and simply a dream, or is it the opportunity for the executive leadership of the COO community to leave a legacy?

Some speak of this legacy in the sense of true obligation and a wish to see the industry they have dedicated their careers to be left in good order for the generations that will follow them. They joined the honourable profession of banking and they have seen its reputation torn asunder, where many in society would still declare it rendered morally lifeless.

Despite best efforts to repair this damage, it remains an industry with a tarnished status and perhaps significantly for its future, no longer the ‘go-to’ industry for the best graduates and therefore the people who are needed to lead it tomorrow.

Therefore, two possibilities exist for the industry’s leadership today and within this spectrum, the COO:

1. The opportunity to be the leadership generation that lived through the banking crash and consequent economic downturn, managed and met the regulatory demands imposed upon it as its consequence, but changed nothing.

Or

2. The generation that responded to this challenge and did something on and above what was required by them in law and from the regulators, to build the foundations for a cultural revolution to take the industry towards a brighter future. A future with a collective, industry wide purpose and vision; one that sits above profit, but complements and contributes to the creation of enhanced and sustainable profits.

Here in rests the opportunity and herein lies the debate.

These are open-ended and lofty aspirations which need a structured and wholesome examination within the COO community to truly assess whether this approach is supported, viable or achievable. The optimists will say yes, and the pragmatists will nod in tacit agreement whilst seeing the hurdles to success as being too high or ambitious. If we were to investigate the above and look for an outcome, there are a few questions that need to be answered:

1. What is the purpose of banking; including your bank and your role as a COO?

2. What is the present approach to conduct, ethics and behavioural training: does it work? If not, why not?

3. What could the COO achieve in cultural change and conduct if given greater empowerment?

4. How much of the core responsibility should lie with the COO, regarding conduct and culture?

5. How do you meet these objectives whilst helping to grow the business, add value to clients and run a safe business?

6. What would be the principles that would enable a COO to manage cultural change?

7. How do the regulators view and position the role of the COO in the context of owning cultural change and co-owning its accountability for its delivery?

In recent discussions, several COOs have expressed frustration with the regulators and specifically the FCA as to the seemingly entrenched view and perception regarding the position and influence within the business of the COO. This impacts the ability for the COO to be taken seriously as an active leader and participant in the external debate and dialogue in relation to conduct, behaviour and, more broadly, managing cultural change.

Most COOs contend that they are firmly 1LOD and this is how the position should be viewed and engaged, not as a dilution or relegation to be anointed 1b or 2LOD. This debate is tied to defining where to place the COO role within the three lines of defence; regulators seemingly holding a contrary view to that of the COO’s, where we can summarise this debate and difference in opinions as ‘1b or not 1b; that is the question’

“We are part of the business, not separated from it. We are the instrument that helps to define and execute the conduct agenda, and an active participant at the leadership table in relation to shaping and driving cultural change. Until we are viewed as 1LOD and not 1b, we will not be able to play our full part in helping the industry to drive cultural change.” (Global COO within Markets)

This frustration is understandable, where the perceived positioning of the COO can be openly seen within the FCA’s summary on Conduct Risk Programmes (Reference: FCA website, first published: 12/04/17, last updated: 21/04/17), as follows: “Conduct risk programmes should be tailored to the needs of each firm based on its:

• Size

• Business model

• Geographic reach While there is no ‘correct’ answer, these features are generally recognised by firms as effective:

• Highly visible CEO sponsorship together with engagement and challenge by the Board

• Senior executives taking leading roles in programme design

• Programmes that cover both front office, control and operational functions

• Detailed roll-out plans with clearly defined short-term and long-term goals

• Clear ownership and responsibility for programme implementation by senior executives, sometimes supported by conduct specialists within the organisation

• Programmes integrated within strategic or operational risk management frameworks

• Use of a standardised conduct risk self-assessment process across the firm

• A firm-wide taxonomy for conduct risk types, enabling consistent data capture and risk reporting

• A forum to compare conduct risk across business lines and functions

• Regular discussion at Board level of conduct, culture and programme implementation

• Active engagement in the programme by internal audit, including monitoring the programme’s early stage effectiveness

• Training, promotion, performance management and remuneration all linked to conduct and culture objectives

• Long-term conduct risk initiatives becoming fully embedded in business as usual

• For international firms, adoption or at least support of the UK programmes from the head office Programmes with the following features did not always generate the desired results:

• One-off or stand-alone projects with a short timeframe

• Compliance or the COOs being the primary driver of the programme

• Top-down mapping of desired conduct outcomes to business-level risks that were not balanced by similar bottom-up efforts by business units to identify where conduct risks could arise

• Disjointed or uncoordinated efforts by different business units

• Significant business units, control or operational functions being excluded

• Not examining if conduct risk arising in one area could arise in another

• Programme focus being limited to front office senior personnel, with limited or no Involvement from middle and back office, risk, control and other support functions

Interestingly the above notes ‘did not always generate the desired results’. However, by its very definition, cases will exist whereby it did. There is additionally the argument that if the COO was mandated and engaged correctly, then such cases of positive affirmation would increase. The COO also reaches into the business front-to-back and therefore can influence, shape and imbue a consistent cultural messaging, where some programmes have most assuredly focused too much on the front office alone.

Naturally, if the COO was to gain this acknowledgement and engagement, it would also attain the burden of accountability and responsibility, perhaps becoming an automatically named position within the Senior Managers Regime (SMR) or Significant Influence Functions, as outlined.

Whether this is desirable for all COOs in position today is unlikely, as this burden is a heavy one to carry, but once depersonalised, the industry may benefit from the COO position being anointed as such. It would also manifest itself in the work to be done in defining what criteria you would reference for any COO to demonstrate they had the ‘experience, competence and knowledge’ to be a COO.

“How we assess applicants for key positions at a firm. We regulate two types of individual:

• Those with significant influence over a firm’s conduct

• Those dealing with customers (or their property)

To ensure firms are effectively governed and able to deal with their customers fairly, only individuals with the appropriate skills, capabilities and behaviours should be appointed to these positions.

Firms must have balanced and effective boards, with a competent executive team, so we consider any appointment in this light.

We assess applicants for key positions to make sure they are up to the job and that they carry out their role effectively. We will continue to take a risk-based approach to approving individuals who perform controlled functions.

For significant influence functions (SIF) in higher-impact firms, we will interview where appropriate. Applicants do not have to sit a formal exam, but we do expect them to be able to demonstrate experience, competence and knowledge in the function that they apply for.”

(Reference: FCA website, Significant Influence Functions. First published: 12/05/15, last updated: 13/05/16)

This approach and outcome would require a mindset shift with the regulators, across the industry and for many of the CEOs and business heads (that may not use and/or see their COO in this empowered capacity).

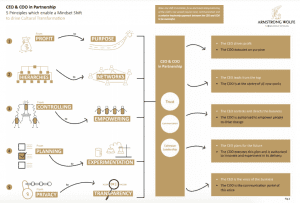

More so, it would require the COO community to embrace this mindset shift and to work with the CEO community to ensure all within the business understand this paradigm shift. (See fig.3)

Any outcomes should therefore be focused on providing:

1. A repositioning and education of the regulators as to the exactness of the COO role as a core component of executive leadership and therefore the 1LOD spectrum

2. A common code of practice by which the COO community align their approach to defining purpose and maintaining, managing or changing culture

3. A COO examination, leading to an accreditation, for any aspiring COOs, which will help prove demonstrable experience and capability*

*This course would focus on personal leadership and accountability, conduct and ethics, and defining self and collective purpose. Additional modules would relate to the core responsibilities of a COO, such as talent and financial management, regulation and technological innovation.

Earlier, I summarised the difference in opinions between the regulators and the COOs themselves as ‘1b or not 1b, that is the question’. This is of course is drawn from the opening phrase of a soliloquy spoken by Prince Hamlet in the so-called ‘nunnery scene’ of William Shakespeare’s famous play, Hamlet. Act III, Scene I

“To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them”

Taking the opening line and changing it to ‘1b or not 1b, that is the question’ was merely a play on these well-known words. In context to this article, its follow-on lines ‘Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune or to take arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing end them’ would appear highly fitting to the challenge facing the COO community and the choice that exists to address, meet and oppose the ‘sea of troubles’ that has beset the banking industry for a decade.